On what must have been an uncharacteristically dark or low day/occasion after the birth of my daughter, after looking —courtesy of Facebook— at the pictures from somebody or other’s gorgeous vacations, I despondently told my father I didn’t think I’d be able to go back to Europe before I was sixty. Something in him (who, I now think with shame, had set foot on the Old Continent for the first time in his late forties) was obviously pained and stirred by my comment. I recalled this several months later, when he smilingly gestured around at our very lovely Amsterdam surroundings and said, “Pray, now, will you tell me how old you are?”

He had engineered this trip for us, paid for it, so that he and my husband and daughter and I could walk along pristine streets and peer into tantalizing windows and absorb a kind of beauty that seemed as if it was happening, uninterrupted, since the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. I loved to see streets named after painters — it felt as if they might saunter out a door at any time, ready for some rest after essentially inventing private history, leading us into houses not ours, across tiled floors and shadowy thresholds, and showing us the daily lives of others in all their endearing ordinariness.

It was he who had tersely overruled our misgivings about taking our toddler daughter with us (“either she comes along or nobody does”), a decision that would prove wise, and good for all four of us. His love for her and understanding of her were unparalleled, and still illuminate her heartscape.

It was not the first time either of my parents had offered me this hugely generous and unforgettable gift of travelling — both of them had done so in more than one prior occasion, helping me grow emotionally and intellectually. But this trip feels especially poignant because when we made it my father’s life had almost completely run its course. There was some plane-hopping still in store for him, yes —including to an affecting class reunion in the United States, where he visited high school classmates he hadn’t seen in fifty years—, but his time on earth was essentially behind him that afternoon in Amsterdam when he basked in the cold spring light, knowing he had given this to us.

He was with us in the Netherlands only briefly, getting on board one of the world’s unsafest airlines (!) after less than two days, bound for a conference in Turkey where he was scheduled to speak about the deterioration of Uruguay’s democracy, which ultimately led to a bloody dictatorship lasting twelve years — a candid, sure-to-be-controversial lecture I had helped him translate into English.

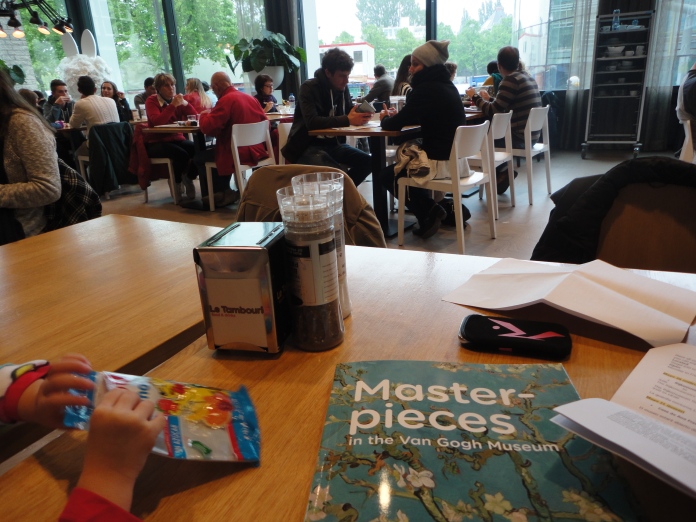

But I think he cherished his short time with us — the drizzly afternoon he came face to face with Van Gogh and was greatly moved by his paintings, later browsing through a catalogue of them at the museum cafeteria with his granddaughter (and helping instill an enduring passion for “Vincent”), or trying to spoon-feed her at a cake shop I’d marked as to-visit and then unexpectedly come across, while I savoured my cappuccino and rain smeared the windows. He cherished sharing an umbrella with me, secretly buying me a little porcelain reproduction of Vermeer’s girl with a pearl earring, or scrawling a loving note to tuck inside a book (Vincent again) he had bought for the little one. I loved having him with us, even if we were often capable of getting on each other’s nerves — our bond was certainly not perfect, but it was one of the most perfect bonds I’ve ever had with another human being.

He broke my heart when he died — not the first man to do that by a long shot, but the first to do it against his will, and, I now see, the only heartbreak that hasn’t mended. He loved life, loved his children and grandchildren, was mercurial and intense and complicated — an uncompromising, no-holds-barred, fiercely intelligent and, above all, decent man. Taking up this blog again, it hurts to know I won’t have the small happiness of his reading me, commenting on my work, or just being out there. But I love to write, and I love to tell stories, and he is a part of mine, of my past and present, the nether and upper countries of my life.