It was a time when other countries were very far away. A time when your knowledge of them, unless you were lucky enough to travel, depended on TV, newspapers, or people who “had been”. When someone wore a foreign brand of sneakers to a party, or brought, say, a showy walkman to school, it was usually a present from an uncle or godfather or family friend who “lived in the U.S.” The item in question was admired and envied. We all dressed more or less the same, owned more or less the same things.

But for me, rather than a source of trendy sneakers, foreign lands were the world of the unknown, and the unknown fascinated me. Also, I loved writing. So I naturally turned to letters, sent and received, as a window onto that world. I was 12, 13, 14, 15 years old, and I had my pen pals. In Finland, mostly.

Had anyone asked me, I could have told them what Finnish kids did after school, the magazines they read, the music they listened to.

Some things were the same. Nina would fancy a classmate who didn’t fancy her and had kissed some other girl at a party. Or Anu would have divorced parents and have to spend Christmas alternately with each of them. But other things were oh so different: Vesa, whose father was a policeman, would spend holidays in Ibiza or the Maldives. Not exactly the life of a cop’s son in Uruguay.

Perhaps the greatest difference, though, was snow: for them, an ordinary part of their lives—for me, something mythical, never seen but marveled at.

My friends’ letters (if the friend was a girl) would often be written on beautiful stationery and include small offerings, like cards or stickers. Japanese stationery was the rage then, in Uruguay as well as in Finland.

But what I loved the most was the glimpses letters gave me into these friends’ lives. Glimpses patiently awaited, as letters flew back and forth across vast continents and oceans. If emails had existed back then, we would probably have run out of things to say at some point, but letters enabled us to build a friendship based on curiosity and expectations, month after month, year after year.

Inevitably, I enjoyed some of these friendships more than others. Pilvi (my name means in English cloud) was from Helsinki, rather shy, and an only daughter. Merja was outgoing and gregarious and did not hesitate to plant a kiss on Tommi’s mouth when he was a bit slow in showing interest.

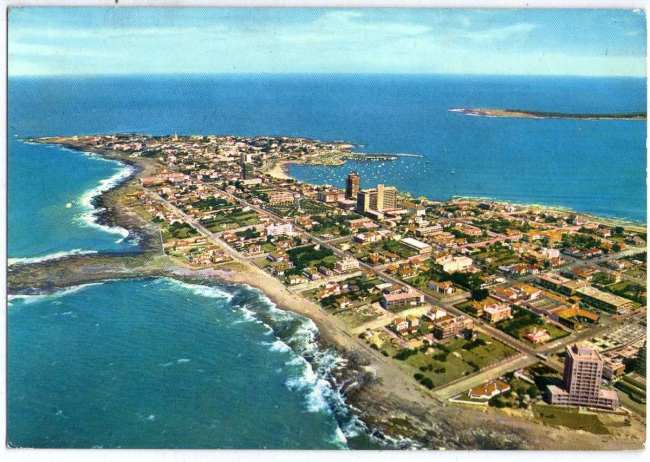

The post office on Ejido Street was huge, badly lit and with grim murals on the walls; the employees, sour-faced and unfriendly. I wanted stamps to be put on my letters, so that my friends would see what our founding father looked like, or our flowers or plants, but more often than not I just got a postmark. I was ashamed of these letters sent out without a stamp, and wondered what my friends in Finland would think of them—of us. To alleviate this and show we were not so drab as these dull postmarks seemed to show, I sent them postcards of beautiful places in Uruguay.

And they, in turn, sent their photos—fair hair and pale eyes—and gave me basic Finnish lessons (minä rakastan sinua—kirjoita pian—paska). And postcards in return for mine.  Dozens of postcards that whisked me away to a mysterious world, to shimmering lakes that gave back the image of the trees, to the pure scent of snow clothing pines in their rose-blue mantles.

Dozens of postcards that whisked me away to a mysterious world, to shimmering lakes that gave back the image of the trees, to the pure scent of snow clothing pines in their rose-blue mantles.